Τὸ ΟΧΙ μέσα ἀπὸ τὸ περιοδικὸ Time

Ἔχει ἐνδιαφέρον ἡ ματιὰ τῶν ξένων γιὰ τὸ ΟΧΙ τοῦ 1940, καὶ μάλιστα ἀπὸ τὴν μακρινὴ Ἀμερική. Πῶς ἡ ἄγνωστη, μικρή, ἀσήμαντη γιὰ τοὺς ξένους Ἑλλάδα, σὲ λίγες ἑβδομάδες ἔγινε ἡ χώρα τῶν ἀρχαίων ἡρώων. Οἱ τίτλοι εἶναι χαρακτηριστικοί: Ἡ «Χώρα τῶν εἰσβολῶν» δίνει τὴν θέσι της στὰ έπιφωνήματα θαυμασμοῦ: «Ζήτω ἡ Ἑλλάς», «Γιοὶ τῆς Ἑλλάδος», «Παιδιὰ τοῦ Σωκράτους»!

4-11-1940: Land of Invasion

Τὸ πρῶτο τεῦχος τοῦ «Time» μετὰ τὴν ἰταλικὴ ἐπίθεσι, μὲ τὸν Βασιλέα Γεώργιο Β' στὸ ἐξώφυλλο. Ἄρθρο ποὺ ξενίζει τὸν σημερινὸ ἀναγνώστη. Τὸ μεγαλύτερο μέρος τοῦ ἄρθρου ἀναλίσκεται σὲ ἀμφιλεγόμενα κουτσομπολιὰ γιὰ τὴν βασιλικὴ αὐλὴ (σὲ ἐπόμενο τεῦχος δημοσιεύεται ἐπιστολὴ διαμαρτυρίας ὁμογενοῦς ἀναγνώστου) καὶ λανθασμένες ἐκτιμήσεις γιὰ τὴν ἐξωτερικὴ πολιτικὴ τῆς Ἑλλάδος καὶ τὸ φρόνημα ἡγεσίας καὶ λαοῦ. Ὁ τίτλος, «χώρα εἰσβολῆς»· οὔτε σκέψις γιὰ ἀπόκρουσι τῆς ἐπιθέσεως.

4-11-1940: Shots at Corizza

11-11-1940: Episode in Epirus

Φθάνουν οἱ εἰδήσεις γιὰ τὴν σθεναρὴ ἑλληνικὴ ἀντίστασι! Ἐν τούτοις, ἀπίστευτο μοιάζει ἀκόμη γιὰ τὴν παγκόσμια κοινότητα τὸ ὅτι οἱ Ἕλληνες μποροῦν νὰ ἀντέξουν. «Παρὰ τὸ σθένος τῶν γενναίων Ἑλλήνων, οἱ Ἰταλοὶ τὰ καταφέρνουν καλά», καταλήγει τὸ ἄρθρο, καὶ ἕνας ὁμογενής μας στέλνει ἐπιστολὴ διαμαρτυρίας, κατηγορώντας τὸ περιοδικὸ γιὰ ἡττοπάθεια!

18-11-1940: Murk

25-11-1940: First Round: Hellas

Ὀ ἀχὸς τῆς νίκης τῶν ἑλληνικῶν ὅπλων φθάνει πλέον στὰ πέρατα τοῦ κόσμου. Οἱ Ἕλληνες ἀρχίζουν νὰ ἀναφέρονται ὡς ἀπόγονοι τῶν ἀρχαίων ἡρώων: «The war was being fought, and its first phase was now won, straight out of antique textbooks.»

2-12-1940: Zeto Hellas

Ἀπελευθέρωσις τῆς Κορυτσᾶς!

2-12-1940: Sons of Greece

Ἡ ὁμογένεια τῶν Η.Π.Α. κινητοποιεῖται καὶ προσφέρει ὅ,τι μπορεῖ στὸν Ἀγῶνα.

9-12-1940: Children of Socrates

16-12-1940: Surprise No. 6

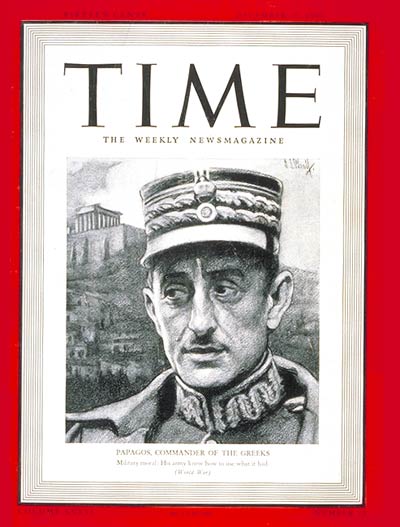

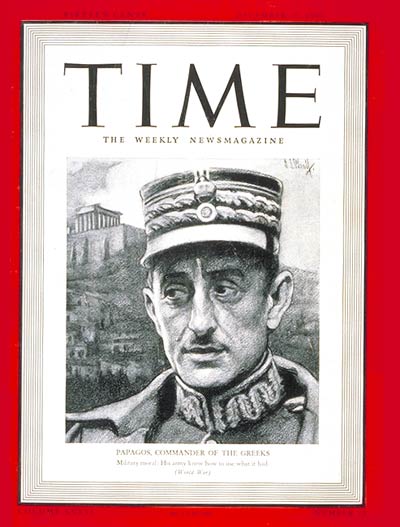

Ὁ κόσμος ὅλος ἐκφράζει πιὰ τὸν ἀνυπόκριτο θαυμασμό του γιὰ τὴν Ἑλλάδα. Τὸ τεῦχος τοῦ περιοδικοῦ εἶναι ἀφιερωμένο στὶς μεγάλες ἐκπλήξεις, μέχρι τότε, τοῦ πολέμου· καὶ μεγαλύτερη ὅλων, γράφει, ἡ νίκη τῶν Ἑλλήνων. Στὸ ἐξώφυλλο ὁ Ἀρχιστράτηγος τῆς Νίκης, Ἀλέξανδρος Παπάγος.

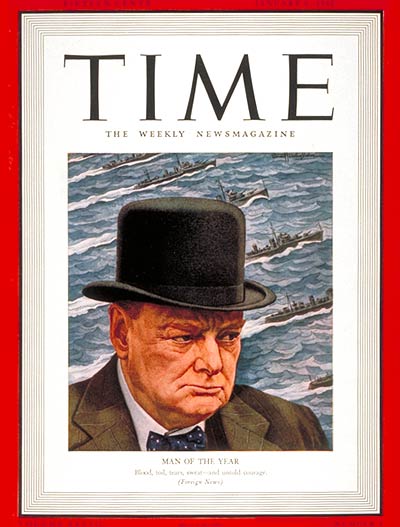

6-1-1941: Winston Churchill, Man of the Year

Ἐξαιρετικὸ ἄρθρο γιὰ τὸν «ἄνδρα τῆς χρονιᾶς» Ουίνστων Τσώρτσιλ. «Μεταξὺ τῶν ὑπολοίπων Εὐρωπαίων ποὺ σημάδευσαν τὸ 1940», ἐπισημαίνει τὸ περιοδικό, «ἦταν ὁ μικρόσωμος Στρατηγὸς Ἰωάννης Μεταξᾶς, Πρωθυπουργὸς τῶν Ἑλλήνων, ὁ ὁποῖος γελοιοποίησε τὸν Μπενίτο Μουσσολίνι.»

27-1-1941: Dominick the Greek

Ἔκθεσις δεκαοκτώ ἔργων τοῦ Δομήνικου Θεοτοκόπουλου, τοῦ «μεγαλυτέρου Ἕλληνος ἀπὸ τὴν ἀρχαιότητα» στὴν Νέα Ὑόρκη. Τὰ ἔσοδα διατίθενται γιὰ τὴν ἐνίσχυσι τοῦ γενναίου Ἑλληνικοῦ Στρατοῦ.

10-2-1941: Wanted: Bone and Gristle

Ἐπικήδειος γιὰ τὸν Ἰωάννη Μεταξᾶ.

10-2-1941: Heaviest, Firmest

Διαψεύδονται οἱ ἰταλικὲς προσδοκίες ὅτι ὁ θάνατος τοῦ Μεταξᾶ θὰ λυγίσῃ τοὺς Ἕλληνες.

17-3-1941: Even Without the Turks

Ἡ Ἑλλὰς εἶναι ἀποφασισμένη νὰ ἀντισταθῇ στοὺς Γερμανούς, ἀκόμη καὶ χωρὶς τὴν βοήθεια τῆς «ἐπιτήδειας οὐδέτερης» Τουρκίας.

21-4-1941: Weakness Defies Strength

Ἡ Μάχη τῶν Ὀχυρῶν τῆς Γραμμῆς Μεταξᾶ.

28-4-1941: 80-Day Premier

Ὁ πρωθυπουργὸς Ἀλέξανδρος Κορυζῆς σφραγίζει μὲ αὐτοκτονία τιμῆς τὸ ὕστατο ΟΧΙ τῶν Ἑλλήνων. Τὸ σκότος τῆς κατοχῆς ἀρχίζει...

Φειδίας Ν. Μπουρλᾶς

Ἀθήνα, 28 Ὀκτωβρίου 2008

(«Time», Monday, Nov. 04, 1940)

(See Cover) Since World War II began 14 months ago the Balkan Peninsula has run a temperature. Periodic scares have sent it to fever pitch, then dropped it as, one way or another, neighboring powers got their way without bloodshed. Rumania is partitioned and overrun by the German Army. Bulgaria takes orders from the Axis. Even Yugoslavia, which has a relatively large, well-trained Army, has taken the path of appeasement. This week war came at last to the Balkans, to the weakest country, but to the one country determined enough to stand up to Axis threats — to Greece.

Hellas has always been invaded. Since the barbarians carried the centre of power from southern to northern Europe she has been a pawn in all great struggles for power. Salonika is a back door to Central Europe, a jumping-off place to the Dardanelles and the Black Sea. Rocky Greek islands straggle across the Aegean to the shores of Turkey. The Peloponnesian Peninsula lies close to Italy; Crete, halfway to Africa. In this war Greece's fate was settled at Brennero on Oct. 4, when Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini planned their drive to the east. For Greece is the key to control of two of the three routes to the east : by land and sea through Turkey, by sea via the Mediterranean. Even the third route is controlled in part by Greece : the capture of Crete would help to safe guard Italy's Libyan route into Egypt.

Only strategic reasons could justify wasting military effort, however small, on Greece. The country is rocky, arid, grows little food. Greece's occasional prosperity has been based on maritime trade, and with the bulk of Greek shipping chartered to Britain, Italy will not get that.

As he defiantly rejected Italy's three-hour ultimatum, Premier "Little John" Metaxas addressed himself to the Greek people in words reminiscent of the days of Byron (see p. 22)

As Greece's poorly equipped, indifferently trained Army fought 200,000 Italian regulars in the mountains of Epirus and Macedonia Little John, who had once been thought an Axis stooge, called for aid from Britain and Turkey. Turkey's President Ismet Inönü had one ear cocked toward the Kremlin, and since his other ear is stone deaf, he did not immediately hear the call. Britain, expecting an attack on Gibraltar any day, sent her Mediterranean Fleet steaming toward the danger area. If Britain lost in the Eastern Mediterranean, and lost Gibraltar too, her goose was much closer to being cooked.

The Mind of Metaxas. Little John Metaxas, who was pro-German in World War I, changed from a waverer to a stiff-backed defier of the Axis after several months of intrigue in that most intriguing country, Greece. Six months ago he was thought ready to sell out to Mussolini. Then Britain, having relearned a lesson in Norway and Belgium that she knew well in World War I, began to put pressure on Little John through the man everybody considers his puppet—Greece's King George II. Britain made it clear that unless Greece agreed to secret staff talks and precise plans for military cooperation, Britain would seize whatever bases she needed. Metaxas agreed, and the Axis turned its attention to another choice for Puppet of Greece: King George's ten-inch-taller brother, Prince Paul, who is married to a German princess. So Greece's George II had his throne at stake when he exhorted his people this week:

"At this great moment I feel sure that every Greek man and woman will do his duty to the end and show himself worthy of our glorious history."

George's father lost his throne in the last war because he was thought to be pro-German. So was George. But George got on his throne in 1935 only because he was Britain's man, so he would have been less than grateful if he had failed to pay his debt. This week's events had a strangely familiar look to the Greek people. In the last war the roles of the great powers were reversed, but the Greeks and their rulers were on the same, receiving end of the trouble.

Kings and Strong Men. Almost from the day World War I began Greece was a centre of intrigue. King Constantine, his eldest son George and his Chief of Staff John Metaxas were accused by the Allies of being pro-German. In point of fact, the King at least was scrupulously neutral. In 1915 the Allies landed troops at Salonika in an ill-starred attempt to save Serbia; in 1916 they shelled Athens to make the Greeks give up their arms; in 1917 they almost starved Greece to force her into the war. Against this pressure and against the quisling tactics of Eleutherios Venizelos (whom the King had deposed as Premier for conniving with the Allies in the Salonika adventure) Constantine could not hold out. In June 1917 he fled the country with his Queen and Crown Prince George. Venizelos returned from exile and declared Greece in the war.

The Allies set up Constantine's second son, Alexander, as a puppet King, with Venizelos as the country's strong man. This arrangement worked well until Alexander happened to be bitten on the ankle by a monkey, ending his career in October 1920, just 20 years ago last week. The next month Greeks went to the polls, expressed three years of resentment against Venizelos by overthrowing the Government. In a plebiscite on Constantine's return, huge and genial "Tino" got 150% of the eligible votes. He returned to Athens at the end of 1920, inheriting a war against the Turks.

He stayed less than two years. France and Great Britain refused to recognize him, he was blamed for the debacle at Smyrna, and after a demonstration led by Colonel Nicholas Plastiras he abdicated again. He was succeeded by Son George, who lasted just 15 months. Venizelos, recalled to salvage at Lausanne what he could from the Turkish imbroglio, could not get along with him; the country soon split into two camps, Venizelists (i.e., republicans) and Monarchists. In December 1923, after a Venizelist victory at the polls, George and his Queen, Elizabeth of Rumania, were asked to leave the country while Parliament decided on the future form of government. On March 25, 1924, 103rd anniversary of the Greek declaration of independence, Parliament proclaimed a republic.

Altogether, between 1923 and 1935, there were 25 Greek administrations plus two dictatorships (one for 14 months under General Pangalos, the other for 14 hours under General Plastiras). In October 1935 an Army coup established General George (The Thunderbolt) Kondylis as Premier and Regent; the republican Constitution was abolished and monarchy restored. After much international political finagling Georgios II was invited to replace his British bowler with the diadem of his forefathers.

Gorgeous Georgios. This twice-enthroned son of a twice-abdicated father had been bored by his twelve years of exile. In London, where he lived most of the time, he liked nothing so much as strolling along through the streets at night —and once he had the distinction of being the first King known to have been solicited by a prostitute. George's preference was for noble ladies, a preference which had caused him to be divorced by his Queen just before his return from exile.

He had been accustomed to the privileged but democratic life of small-time royalty. The Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg family, which ascended the Greek throne in 1863, had the easygoing habits of all Danes. George grew up at Tatoï Castle, 15 miles from Athens, whence came the family eggs-&-butter; at Mon Repos on the island of Corfu, where his grandfather always spent the month of April because Kaiser Wilhelm II used to go there in April and Georgios I said: "If I don't, he'll think he's King of Greece"; and in the Athens Royal Palace, a gaunt structure of stuccoed white marble. George II's Uncle Christopher had a sense of humor, wrote of the Palace:

"It was hideous—like a huge cardboard box. . . . There was only one bathroom in the whole place and no one had ever been known to take a bath in it. ... The taps would scarcely ever run and emitted a thin trickle of water in which the corpses of defunct roaches and other strange animals floated dismally. . . . The Palace in itself would have been a joy to any child. The long, dim galleries and unused rooms made endless appeal to the imagination. The vast entrance hall and the grand staircase were ideal for hide-&-seek. Then the delight of bicycling on wet afternoons through the enormous ballrooms. . . ." Georgios I used to lead the bicycle procession, his children and grandchildren following in order of age. Uncle Christopher, Constantine's younger brother, was only two years older than Grandson Georgios and was his playmate. When they were 21 and 19 they paid a giddy three-weeks visit to Buckingham Palace and were trotted around by Uncle Edward of Saxe Coburg-Gotha.

George served in Uncle William Hohenzollern's Prussian Guards for a time, fought in the Balkan Wars of 1912-13. In 1913 Grandfather Georgios was assassinated and Father Constantine became King. By 1917 George was a Major of infantry and Commander in the Greek Navy, but his father's abdication kept him from doing anything in the last war. George drove off in one of the fleeing cars, lying on the floor with his legs waving out of the open door. For the next 18 years (except for his brief puppet reign in 1922-23) he was out of a job. He once described himself as "one of the unemployed who hopes to get his job back."

But in 1935 George suddenly found himself internationally important. Italy's man in Greece was the old Thunderer, George Kondylis, who was serving as War Minister. George became Britain's man. Premier at that time was Panagiotis Tsaldaris. George's family gave a banquet at Bled, Yugoslavia, for Premier Tsaldaris, who went into dinner a republican, came out a royalist. That put the squeeze on Kondylis, who helped to rig the plebiscite that recalled George by a 98% vote. The Royal Family and Michael Arlen saw him off from London. He set foot on Greek soil on Nov. 25, 1935. Athens was decorated with arches on which republican youths spattered ink. Royalist youths chipped in to buy the King a Royal Bed.

Rise of Little John. When the shouting was over Greece was in just as bad a political mess as ever. Kondylis wanted to be a Duce; George wanted to be a real King. He dismissed Kondylis (who shortly died), called for free elections. The elections only made things worse. Venizelists and anti-Venizelists were almost evenly divided and the balance of power in the new Parliament was held by 15 Communists. Venizelos and Tsaldaris, who might have helped the King to maintain constitutional government, died. Thereupon George called on War Minister John Metaxas (whose party held seven seats) to form a Government. Metaxas did. To avoid a test vote he persuaded the King to dissolve Parliament. Next day Metaxas reorganized his Cabinet, abolished political parties, imposed a ferocious censorship. In 1938 he made himself Premier for life.

Little John has not been popular in Greece. His Government is neither a constitutional monarchy nor a corporative State, but it has those fascist elements of regimentation, government by decree, secret police and a youth movement. There are no civil liberties, but cigarets are cheap and every man can afford a string of beads to twiddle in his idle fingers. Metaxas is Premier, Minister of Foreign Affairs, Minister of Cults and National Education, Minister of War, Minister of Marine, Air Minister. His chief hold on the King is a little secret between them: the King, who is always hard up, signed a decree paying himself his salary for the years of his exile, and the King knows that if Little John gets mad he will spill the story to the country.

Bone and Gristle. Fifty-year-old George is childless, disinclined to marry again. Once he was reported engaged to the Countess of Craven. The Countess' mother denied the rumor, but added: "I may state, however, that my daughter and the King of Greece have been close friends for about 15 years." A year before that, while Edward VIII was cruising in the Adriatic, King George invited him to dine with him—"alone." Cousin Edward arrived with Mrs. Simpson. A few days later Edward invited Cousin George to dine with him alone. George arrived with his friend.

Neither family life nor intellectual pursuits interest the King of Greece. He loves circuses, once rode in one as a boy. He likes to drive a car fast, to shoot big game, to dance, go to first nights, wear snappy clothes—stripes and braided uniforms.

This week modern Greece had, for better or worse, stepped out of her comic-opera role. Greece was full in the path of huge events. In a debate at the Oxford Union during his exile George once said: "Instinctively I distrust the professor and the pedant. Give me a burly man of bone and gristle." This week the men of bone were on the way.

Ἐπιστολές («Time», Monday, Nov. 25, 1940):

Sirs:

. . . In TIME, Nov. 4, discussing King George II of Greece, you say: "Once he had the distinction of being the first king known to have been solicited by a prostitute." Now after all, dear sirs, are not you being a wee bit quibbling, a wee bit naïve? I know you are quite an authority on history, but are you not being somewhat egotistical and somewhat irreverent toward other great and probing historians when you make such an assertion?

HENRY STONER

(«Time», Monday, Nov. 04, 1940)

The Italian Minister to Greece gave a party in Athens one evening last week.

Though relations between his country and Greece have been strained ever since a mysterious submarine sank the old Greek minelaying cruiser Helle during a religious festival last August, he invited members of the Greek Government. The party was in honor of the son of the late great Italian composer, Giacomo Puccini, whose opera Madame Butterfly was being performed in Athens.

Ominous to Greek ears was another Italian sound-effect they heard that evening — from Mussolini's news agency, Stefani: news that there had been a "border incident" that day near the Corizza Pass on the Greek-Albanian border, and a bomb incident at Porto Edda (named for Il Duce's daughter). The Italians, of course, blamed Greek "armed bands" and agents. Denial of the affairs by the Greeks went unheard, their offers of discussion were turned down. Within a few hours Mussolini and Hitler had one more conference, at Florence (see p. 28), and Italy's war machine in Albania began to roll. Greece was soon officially charged not only with local violence but with plotting to give Great Britain the use of sea and air bases for operations against Italy. At 3 a.m. on Oct. 28 the Puccini-loving Italian Minister handed to Greek Premier General John Metaxas a three-hour ultimatum demanding surrender of Greek territorial integrity. Metaxas refused it and addressed his people:

"Greeks! We shall now prove whether we are worthy of our ancestors and of the liberty which our forefathers secured for us.

"Fight for the fatherland, your wives, your children and sacred traditions.

"Now, above all, the fight!"

It was Monday, the day on which: the Russo-German pact was announced; Italy entered the war; France laid down her arms; the Italian conquest of British Somaliland was completed.

With a population of 7,100,000, Greece has 140,000 active soldiers, 600,000 reserves, equipment for only 150,000 in the field at one time. Before coffee time on Oct. 28 the streets of Athens rattled and rumbled with trucks and busses rushing hastily mobilized men northward toward the Pindus Mountains.

Greece has a Metaxas Line, strong along the Bulgarian frontier, more sketchy along the Albanian, where it was not needed until Italy blitzkrieged that little kingdom on Good Friday, 1939. Greece has some 435 pieces of field artillery of all types, including mountain guns. With these, and other ill-assorted German and French rifles and machine guns, she set out to try to stem the advance of at least 200,000 well-equipped, motorized Italians, including one division of specialized Alpini, whose first course would be down rugged mountain troughs. Two main immediate pushes seemed to be on the cards: one starting near the southern extremity of the Greek-Albanian border, toward the immediate objective of loannina, the other at the northern end of the frontier, near Yugoslavia, with Salonika the ultimate goal.

Greece has about 100 fighting airplanes, mostly obsolescent. Over Athens that first morning roared six waves of Italian bombers. They spared the capital but bombed its airport at Tatoï, its port of Peiraeus. They also bombed the Corinth airport, the harbor of Patras. The Greek Navy-one old cruiser, twelve destroyers, six submarines—assembled at Salonika and watched for attackers. From the mountains came word that the Italian legions had reached the Greek pillboxes. Another war of pygmy versus juggernaut was well begun.

But the pygmy had friends. From Crete and Corfu came word that units of the British Fleet had raced in with landing parties. The Corfu landing followed a sharp sea engagement with the Italians.

On a little isle near Corfu is a military airport, which the British seized. From Turkey came word that Britain's Chief of Staff of the forces in the Middle East, Major General Arthur Francis Smith, was conferring with the Turkish General Staff.

The pygmy also had its nerve about it. The British news agency Reuters reported from Athens that Greek troops had sliced through Italian positions at one point and driven eight miles into Albania. But at other points the Italians did the slicing.

Italy's logical military objectives are in order: Salonika, Athens, Corinth, Crete, to push the British out of the Aegean. If Turkey should give trouble, Italy's partner Germany lurked on Turkey's right flank across Bulgaria in Rumania. Thus the firing in the Pindus Mountains signaled a winter Axis drive of major proportions, aimed ultimately at the Suez Canal.

(«Time», Monday, Nov. 11, 1940)

War seemed good to the Athenians that first day. It was like a holiday. Because of air-raid alarms the shops were closed.

Bands of enthusiasts walked the streets shouting lusty jests, sticking their thumbs up, singing songs, crying the ancient boast: "We will throw them into the sea." They laughed about the macaroni-men from macaroni-land, trying to be warriors.

The people cheered when they heard what the Generalissimo, Alexander Papagos, had said: "We will write new, glorious pages in our history, and do not doubt that we will win our cause." The people were gay when they read on walls the slogans of Premier John Metaxas: "Only pessimistic peoples disappear! Greeks, be optimists!" They trooped to the British Legation, waving the Union Jack beside the blue & white flag of Greece. They cheered until Britain's tall, immaculate Minister Sir Charles Michael Palairet came out on the balcony. Some among them retold the old saw about the time when Sir Charles skied over a Rumanian precipice and was found hours later with his leg broken, his monocle still in place. Just like the plucky British, they said.

They rushed on to the Turkish Embassy, and waved the crescent & star beside those other two fine flags. It was the Turkish Republic's 17th birthday, and they had heard that in Ankara the paper Ulus had said: "We prefer the hell of war to a dishonorable peace." Just like the stubborn Turks, they said.

When they saw King George II driving out in his uniform of Supreme Commander, they cheered and wept. When they looked out across the city to the heights where the ancient temple columns stood in rows like sturdy fighting men, they were proud to be Greeks.

Even on the second day, war was almost fun. It was thrilling to see every taxi, truck, cart, bus and private auto in the town bumping off over the rough road that leads to Thebes and the fighting fronts north and west—vehicles carrying all able-bodied men from 20 to 43 years old. It was a lark to hear that 20 British aviators who had been interned when their planes landed in Greece were now released; and to carry them through the streets like heroes. It was stirring to crowd into Constitution Square before the Hôtel de la Grande-Bretagne to cheer King George emerging from the palace opposite. It was moving to learn that Venizelist officers disgraced in the revolt of 1935 had now pleaded to be sent to the front; and to learn that foreigners, especially Greek-Americans, were signing up: men like 36-year-old John Theotocki, a hash king from Kansas City, who said: "We cleaned up the gangsters in the United States and now we've got a tougher job here." But when the Athenians heard that the Italians had sent their bombers over other Greek cities, that Greek women and children had perished, war was not such fun.

When they considered the odds, when they learned that the Yugoslavs could not help the Greeks unless the Turks did and the Turks would not move until the Russians told them to, when they realized how little practical support the British could give, they were grave. They gathered in coffee houses and drank thick Turkish coffee and sipped their ouzo, as colorless and full of kick as corn likker.

And they talked. Every man gave his opinion, every man was an amateur oracle.

Double Talk. In ancient times two black doves took off from Thebes in Egypt.

One flew to Libya, the other to a grove at Dodona in Greece. In the grove the latter proclaimed in human words the need for an oracle of Zeus on that spot.

From then on priests listened to the rustling of the trees, interpreted, and gave ambiguous oracular opinions. For instance, a general would be told that if he attacked across the mountains of Epirus, a kingdom would fall. Encouraged, he would attack —and lose his own kingdom.

Last week, as the Italians attacked across the mountains of Epirus (aiming in one place for loannina hard by Dodona), there was very similar double talk in the air. It came from "neutral sources." Just as the world heard (via Stockholm) that Finland was victorious to the day of its defeat, heard (via Berne) that France was doing not too badly against the Nazis, heard (from Stockholm again) that the British were throwing the Nazis out of Norway, these "neutral sources" (Belgrade was now the worst offender) gave out good cheer for Greeks. The "news" they told must have come from the rustling of trees—and very possibly those trees were on the Wilhelmstrasse, where so much phony, later demoralizing "good news" has been cooked up.

Had Belgrade's dispatches been true, the Greeks would have been victorious in no time. On the first day of the war, Turkey was said to have declared war against Italy, Turkish troops were said to be entering Thrace. On the second day, Britons were said to have landed in force at Salonika (three days' sailing time from Alexandria, the nearest British base). By the third day a revolt in Albania was said to have reached serious proportions: 3,000-4,000 well-armed rebels were said to be cutting Italian communications from the rear. All this time Greek resistance was said to out-Thermopylae Thermopylae, and on the fifth day Belgrade reported the Greeks "smashing into Albania." This week the Greeks were reported to have invaded the invaders' territory almost as far as the base at Corizza, to have taken 1,200 prisoners, including two generals, and to be on the point of wiping out 15,000 men.

This untempered optimism about the jack rabbit's chances of licking the bulldog was too persistent a phenomenon of World War II to be entirely accidental.

Hills of Hell. That this "neutral" news was fabricated and exaggerated did not take away one jot from the performance of Greece. The mere fact that Greece chose to oppose the Axis juggernaut defied belittling; it was magnificent.

The odds were appalling: 250,000 Italians against perhaps 150,000 Greeks; the fourth biggest navy in the world against one obsolescent cruiser, ten destroyers, 13 torpedo boats, six submarines and a few miscellaneous craft; 500 modern planes and as many more in reserve against perhaps 200 old crates (Junkers, Gloucester Gladiators, Blackburns, even French planes); the tacit support of Germany, with some 70 divisions of 1,125,000 men poised in the Balkans (according to British sources), against overt help from Britain, militarily pinned down at home and in Egypt. Despite this apparently overwhelming disparity, the Greeks chose to fight. Ancient valor was reborn.

There were five main spearheads to the Italian attack (see map, p. 26). The most important Italian effort was aimed at Ioannina, in Epirus. Homer located Hell in Epirus, and the Italians saw why last week. It is only about 35 miles as the airplane flies from the Albanian border to Ioannina; but on the ground the miles stand on end. The terrain is violently mountainous. There are no railroads, and most of the roads are little better than shepherd trails. The area is crisscrossed with low valleys, and last week torrential rains made horrible mud ponds of the roads. It was no country for swift, mechanized, aircraft-supported lightning war.

It was country through which infantry, engineers and pack-mule armament had to make their way inch by soggy inch.

The Hellenes were Hellish too. They had carefully mined the roads and primed the bridges with TNT—and, unlike the Dutch and French, apparently did not forget to touch off the charges. Greece's Metaxas Line—pillboxes, barbed wire, trenches—was ironically strongest opposite neutral Bulgaria; nevertheless it offered barriers. The first line ran from Fiorina to the sea. The Greeks furthermore diverted streams on to roads, used every hillock and rock for sniping. Italian Alpinists are among the best mountain troops in Europe; but the Greek evzones—picturesque, wiry men in white jackets and kilts, slippers with turned-up toes and pompons, and any old sort of rifle—are tough and brave.

But the Italians managed to creep along. Early this week they were at the gates of Ioannina. The spearhead was eventually supposed to go to Larissa, whence a railway and a good highway lead to the Attic peninsula and Athens.

Farther north another spearhead drove toward Fiorina, whence another railway leads to vital Salonika on the eastern coast. Greek counter-raids against this northern drive did get to Albanian soil, and did cause the Italians some embarrassment at their rear.

"Where Are the British?" asked the citizens of Greece on the war's fifth day, when there were still no signs of pledges fulfilled. Athens was treated late that day to the sight of a huge R. A. F. Sunderland flying boat which had previously been interned, and crowds cheered at the sight.

At week's end in London, First Lord of the Admiralty Albert Victor Alexander announced that Britons had landed on Greek soil (presumably on some Greek islands) and he promised vaguely: "What we can do we will do." What the British could do was not much. In London there was some suspicion that the Greek war was a mere feint, intended to draw British strength from Egypt, paving the way for an Axis drive on vital Suez. The Italian attack was in fact no feint, but the British could take no chances. The Salonika campaign in 1915-18 required 157,000 men, and Britain now could spare nowhere near that many. Large-scale land action was out. So far as naval action went the prospects were brighter. If the British could consolidate themselves on the Greek islands they had a much better chance of staying in the eastern Mediterranean. If they were cagey, they might even draw the Italian Fleet into the long desired open battle. Britain could also afford some air assistance. British planes were said to be taking part in raids on Porto Edda, Tirana and Durazzo in Albania, and last week this British craft—probably carrier-based Blackburns—bombed Naples to give the Italian foot its first stings of war. The glowing crater of Vesuvius lighted the way to blacked-out Naples.

But if Britain could give no more help and if Turkey continued indefinitely to play wallflower, the Greek cause looked dim, no matter what bravery or what initial successes the Greeks might show.

For Italy the campaign was vital. Italian bases in Greece could neutralize the Dardanelles and negate Turkey's British sympathies. An Italian Crete would make the eastern Mediterranean very hot water against the plates of British vessels. An Italian victory would eventually mean a Greater Albania which would sew up Italian domination of the western Balkans.

But the most important point of victory in Greece was to give the mouth-watering dictators another little slice off the enemy's cake. Gradually the Axis was consolidating the Mediterranean as it had already consolidated Europe. With Britain out of the Mediterranean, the Axis would be much harder to beat.

The Italian Army is regarded by military men the world over with emotion ranging from contempt to hilarity—almost nowhere with admiration. But this was the first real test. Ethiopia, a war against men whose only armor was the loin cloth, was no test. Neither was the Italian picnic in southern France. No one knows how enthusiastically the campaign in Egypt has been pursued. But this was war, and all the world was watching. Considering the terrain, the weather, and the vigor of the brave Hellenes, the Italians were doing all right.

In any case, Britons who took great heart from reports of initial Greek successes, who argued themselves into the belief that Italy had bitten off more cake than it could masticate, were wishful thinkers. The London Times argued — as it had many times before — that the Axis gamble was really a British success. "Surely," wrote the sober New Statesman and Nation, "we remember the Times saying something very like this before. When the Germans went into Norway they dangerously lengthened their flank. If they are not careful they will become all flank as far as Gibraltar. ... If the Nazis were to reach London Bridge it would be a British triumph. The Times would explain that by so dangerously lengthening their flank they had stuck themselves in one of the least salubrious parts of London, that they would find it difficult to get a respectable meal in the district and that they would use up a lot of their scanty oil resources in getting the Tower Bridge up and down."

Ἐπιστολές («Time», Monday, Dec. 02, 1940):

Paraphonia

Sirs:

TIME and Mussolini seem to have a common source of information as regards the strength of the Greek Army. . . . Both regarded Greece as a pushover. Having discounted her strength in your issue of Nov. 4, you find it necessary in your current issue [Nov. 11] to discount reports of Greek successes and chances of final victory. . . .

Accounts of heroic exploits published daily in the papers give a measure of Greece's determination to fight to the finish and her cause deserves a more sympathetic treatment by Nothing Sacred TIME, whose accounts constitute a paraphonia (sour note to you) in the echo of almost universal acclaim. . . .

EUTHYMIOS A. GREGORY Aiken, S. C.

Sirs:

Your write-up of Greece . . . is especially interesting in view of my former residence in Greece, part of the time in Salonika and part in Athens. I . . . was acquainted not only with Greek soldiers and officers and ordinary Greeks, but also with many high officials. I have two decorations from the Greek Government.

Your jocular spirit is justified, though I know another side. What I object to is the distorted picture you give of Venizelos, whom I knew personally. He is the one outstanding figure in the comic opera, who, as President Wilson said, rose to the height of one of Europe's greatest statesmen. "Quisling" is not a word to be used of him.

JOHN C. CRANBERY The Emancipator

Georgetown, Tex.

[Ἀπάντησις τοῦ περιοδικοῦ]

> All praise to the brave Greek Army and still more praise if it can in the long run defend independent Greece from the much bigger and much better-equipped Italian forces.—ED.

(«Time», Monday, Nov. 18, 1940)

Rain and terrain are wonderful allies. Bad weather and forests helped Finland. Good weather and open country betrayed Poland, the Lowlands, France. Through such mountains and such torrents as northwestern Greece possessed, last week there could be no such thing as Blitzkrieg.

High winds blew sleet and straight-driving rains over the whole war area. These stopped machinery but not mules and men. The rains of Greece make even peaceful travel slow. When he went through Epirus in 1809, Byron wrote his mother: "Our journey was much prolonged by the torrents that had fallen from the mountains and intersected the roads." Successful conquest of these mountainous, slippery areas would have to be brought about on general principles of caution and surprise which have held ever since Hannibal crossed the Alps. Even against an inept enemy, the Italians probably could accomplish this conquest only after weeks, possibly months. The brave Greeks were far from inept.

They fought with elemental fierceness. The lair was threatened. They captured heights by making draft animals of themselves. Even the women dragged cannon behind them. In charges the hairy evzones came screaming, their white skirts flapping like osprey wings. There was no thought —as there often was among the Italians —for personal safety. One young Greek aviator, out of ammunition, flew his plane smack into an Italian plane.

Command of this fury was in the hands of a strangely mild aristocrat. General Alexander Papagos, whose thin face and batwing ears bear a striking resemblance to those of Spain's ex-King Alfonso, inherited from one of Greece's first families a gentle education and gentler manners. But he seemed to give his troops both courage and the initiative of which upsets are made.

The history of 1940 has taught, among other melancholy lessons, that valor plus vigor do not equal victory. While they took heart at apparent successes, responsible Greeks thought that if their country was to survive despite the odds, it would owe its survival to British assistance and to Italian asininity. And responsible neutral observers could not see how either could be great enough to give Greece anything but a reprieve.

Britain's help began to take on clearer form last week. It was clear that Britons had landed at Crete, and some other Greek islands. In London a £5,000,000 loan to Greece was announced. The R. A. F. was really active. Gloster Gladiator fighters patrolled over Greek cities, and bombers hit at Naples, Brindisi, Taranto and Albanian bases. The first British casualty was announced: an R. A. F. gunner, wounded in the head by what was described as a "stray bullet" from an Italian plane. British naval vessels arrived in Athens from Alexandria, carrying a few troops. Very useful in surprising and checking the Italians was a set of light anti-tank guns flown in apparently from Palestine. The British were happy to give all this, since it fitted like a helping hand into the glove of British grand strategy.

Italy's military bumbles are classic. The heroes of Caporetto and of Guadalajara showed in Greece that they had not changed. They simply did not understand the arts of war, much less the politics of war. They knew that Greece was about to have three months of poor weather, and yet they attacked with tanks and planes. Daily they undertook small attacks which they should have known must fail. At one point Italians shelled their own retreating columns. They badly underestimated the Greek will to resistance, and seemed almost positive that Greece would pull a Denmark or a Rumania. A captured Italian officer, Lieut. Quarantino Marco of Parma, was quoted as saying:

"We had no idea war was coming. . . . On the dawn of Oct. 28 we were packed into a sector opposite Fiorina. Our colonel assured us ... that Metaxas [Premier of Greece] had told [Foreign Minister Count] Ciano that the Italian Army had received permission to cross Greece and Yugoslavia. He said Greece and Yugoslavia had joined the Axis and that Greece would never oppose our might." So when the lieutenant's regiment marched up to the Greek border, it was cut to pieces.

In Rome there was puzzlement at the checks which the Army suffered. The populace wanted successes. Even the Army was a little puzzled. Chief of the General Staff Marshal Pietro Badoglio, who saved Marshal De Bono's bacon in Ethiopia, visited Albania to look things over, and this week General Ubaldo Soddu, Vice Chief of the General Staff, was put in command of operations. Reinforcements were rushed into Albania and a large-scale attack predicted when the weather cleared.

Three Sectors. Italian bumbles gave Greece occasion to claim great victories. With the cutting rain hampering iron and steel, soft Italian flesh exposed itself. Although reports fortnight ago of the Greek counterinvasion of Albania, at the northern extremity of the front, were grossly exaggerated, the Greeks had at least temporary successes near Corizza.

In the Corizza sector the Italians apparently opened their invasion with a forked drive, one prong heading for Fiorina, the other for Kastoria. The Greeks hid away in forests and mountains, let them through with comparatively mild resistance. When the advance column of Italians had passed, the Greeks filtered through and fought their way to heights from which they could shell the town with 6-inch howitzers (actually they could almost shell the town from Greek territory). Thus they threatened the Italian rear and automatically stopped the supplyless forked drive. For two or three days the Greeks enjoyed their advantage. But late in the week the Italians attacked them with dive bombers, and their position seemed less enviable. Early this week rain kept Italian planes on the ground.

In the central sector the Italians drove a wedge into Greece which was eventually intended to turn southward and meet a second, coastal wedge, surrounding Yanina (Ioannina). The central finger bored up the precipitous Aoos River valley, reaching its metal claw deeper into Greece than Yanina is. To get this far the Italians must have cracked at least part of the Metaxas Line—concrete trenches, artillery emplacements, rock-hewn machine-gun nests built last year and this under British supervision. The mechanized Italian "Centaur Division" took part in the Aoos drive. At week's end, by which time the Italians were approaching the headwaters of the Aoos, the Greeks claimed the greatest victory of the war. Some 15,000 Italians were said to be surrounded and on the point of capture.

Into the craggy, roadless fastnesses of the Pindus Mountains the Italians were reported to have sent tanks and other mechanized equipment. The Greeks used horse cavalry, played hide & seek with the invaders in territory their troopers knew like the backs of their hands. The Italians, they reported, were mousetrapped and divided into small units, became easy prey of Greek mountain infantry.

On the Adriatic coastal plain, the Italians succeeded in driving a bridgehead across the Kalamas River, and in sending patrols several miles beyond the river. But this week the Greeks, greatly aided by the rain, claimed to have succeeded in pushing the enemy back to the bridgehead.

These successes heartened the Greeks, but it was hard to see how they could last. The long-range odds were too great. Reporting of the war was weird. Whether for reasons of propaganda or because of overanxious sympathy, Greek advantages were overstated. Successive Greek "victories," when traced on the map, sometimes turned out to be steady Italian advances. A mysterious bombing by Italian-type planes of Bitolj, Yugoslavia, which caused a stir of feeling and was followed by the resignation of the Yugoslavs' anti-Italian Defense Minister, General Milan Neditch, may have been a punishment for grotesquely pro-Greek accounts of the war emanating from Belgrade. Qualities of fantasy crept into the dispatches. The Italians were said to be deserting in droves, drowning themselves in flooded gorges, perishing of cold and hunger, suffering from the forays of wolves.

Through the murk of biased reporting on both sides, just one fact shone bright as an ancient Greek fire beacon. Adolf Hitler has an unearthly way, not only of beating his enemies, but of getting his allies into embarrassing wars which make his own successes seem greater. Winter in Finland and the rainy season in Greece were two good examples.

(«Time», Monday, Nov. 25, 1940)

A one-eyed man in riding boots and breeches and a dark whipcord tunic looked down on the sparkling sea from a huge plane. He had finished reading his dispatches. The steward came along the cabin balancing a tray. "Tea, sir?" The man declined it. Then with a pleasant sigh the man leaned back in his seat, opened a book of Browning's poems, and lost himself.

The poetry reader Was General Sir Archibald Percival Wavell, Commander in Chief of Britain's Middle East Forces, on his way to Crete to inspect new British establishments there. At Suda Bay he heard reports from the expeditionary officers and toured gun emplacements. One of the huge guns was fired, and Cretans who stood around cheered and clapped as if an Italian ship had been sunk before their eyes. They talked exultingly of Suda Bay as "an eastern Gibraltar." Sir Archibald heard with satisfaction of the raid on Taranto (see p. 20), of R. A. F. cooperation in Greece, of the wonderful work of the Greeks themselves.

That the man responsible for one of the most crucial theatres of war should have passed tense hours reading poetry was altogether fitting. He was flying to help the Greeks, and poetry was being made in Hellas. Theirs was a battle which wanted Homer, a cause which heeded Byron: Better to sink beneath the shock Than moulder piecemeal on the rock.

Dead Romans. High in Metsovo Pass, embracing the mud, a young Italian lay with his head and chest crumpled by machine-gun fire. No Italian had charged farther than he into Greece. Spread-eagled behind him were more of the dead. They wore green jerkins, they had mountains of kit on their backs, they all lay on their fronts in blood, all kissed the earth. One dead Roman had his arms around a tree. Young boys lay with their pants still creased. Tin hats were crushed and the heads under them. Farther down, materiel, the proud stuff of conquest, lay around—trucks disguised with a sweet artistry of cypress leaves, trailers burned out and pushed aside, wrecked tanks which had spewed out their metal guts.

The dead were in little groups. They had been well dispersed. In the forests farther down they lay sprawled on leaves, and around them like more leaves lay intimate papers and pictures of relatives.

And all around them in the mud were footprints—Greek footprints.

Still farther down unshaven, red-faced Greeks marched toward the invaders with fixed bayonets. Near them trudged their women, erect with food and even ammunition balanced on their heads; and their mules, diamond-hitched with heavy loads. Much farther along, the front-line toilers did their work.

Out in front the Greeks attacked all week. Italian dispatches said that stories of Greek victories were dirty British propaganda—but Italian communiques, if they said anything about the war, said: "Greek attacks were repulsed. . . ." An invasion is not made up of defenders' attacks.

The war was being fought, and its first phase was now won, straight out of antique textbooks. The Greeks found in these first weeks of the war that the newfangled trappings of war were traps for those who used them in this terrain. The Greeks reverted to an old tactic: with bayonet and grenade they stormed heights from which their fire drove the enemy out of valleys below. With this tactic they pushed the enemy back on the central Pindus front. With necessary modifications of this tactic they pushed the enemy back of the Kalamas River on the flat coastal front. Devout Greeks, remembering that Italians had invaded Albania on Good Friday and sunk the cruiser Helle on the day of the Feast of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary, saw Providence in the Kalamas River's first flood in 128 years. Using the same device they pressed their counterinvasion of Albania on the northern end of the front. Corizza (see map, p. 21) was on the point of falling as the week began, was still about to fall as it ended. The reason for the delay was simple: Corizza lies in the centre of a bowl of mountains. The Greeks could not rush down into the dish until they had patiently stormed the entire rim, or else the Italians would do to them just what they had been doing to the Italians. This week Athenian reports claimed Corizza partly won.

"I will never turn back." The first round had clearly gone to the bantamweight. Now it was up to the heavyweight to move in again. Whether the second round would be another story was anyone's guess, but that the Italians intended to try was certain. At Innsbruck Italian and German Commanders in Chief Pietro Badoglio and Wilhelm Keitel met and talked strategy. It must have been an embarrassment to both these old soldiers to consider that if the Italians could not knock over the Greeks by themselves, the Germans might have to come in through Yugoslavia. This week Italians sent wave after wave of planes to strafe Greek positions everywhere, and concentrated tanks near the Yugoslav extremity of the border.

Having led with his chin, Benito Mussolini stuck it farther out than ever this week and defiantly broadcast to the world: "Greece is a tricky enemy. . . . Their hate is profound and incurable. . . .

"With absolute certainty I tell you we will break Greece's back. Whether in two months or twelve months, it little matters.

. . . Whatever happens, I will never turn back."

(«Time», Monday, Dec. 02, 1940)

The sound of distant church bells pealed for half an hour one day last week over the brown hills of Greece—by state decree. In Athens, traffic cops stopped cars to tell drivers what had happened. Newsboys shouted it, innkeepers told their guests. A commemorative postage stamp was ordered. Greek and British flags broke out everywhere and men in British uniforms were carried aloft by cheering, singing Greeks. In the northwest, on the other side of the tumbled Pindus Mountains—a place almost as hard to reach from Athens as the other side of the Rockies is from Washington, D. C.—the little catamount Greek Army, supported by the R. A. F., had finally taken Corizza, advance base for Italy's "invasion" of Greece and the third largest town in Albania (pop. 26,000).

For a week confused dispatches had reported the city falling, then not falling, then falling some more. At last, Premier General John Metaxas appeared on the steps of the Army Headquarters building and officially announced the news that drove Athens wild. From London, Prime Minister Churchill, ever apt, saluted: "This recalls the classic age. Zēto Hellas (Life to Greece)."

Corizza is the crossroads through which Italy, unless she violates Yugoslav neutrality and goes around by the Monastir Gap (Bitolj), must pass to strike at Salonika. It is also a gateway to loannina (Yanina) and the long rough road to Athens. Pounding and pushing the Italians out of Corizza was a feat of which the strategic importance overshadowed even the valor of the men who did it. The town stands at an elevation of 2,500 ft. on the western scarp of the Morava heights. Its defense against assault from the west and north, whence Italy must try to come back or lose what remains of her sorry face, is made easy by artillery planted on Morava and on Mount Ivan.

Corizza possesses two of Albania's best military air bases (others are at Tirana, Valona, Durazzo, all near the coast). Not only by heroic uphill righting but even more by knowing from lifelong habit how to get around in the hills, the evzone ("well-girt") highland Greek regiments—Balkan counterparts of Scotland's kilted "Ladies from Hell"—took these commanding positions one by one from the Italians, clambering over the top of the mountains with bayonets and hand grenades, later laboriously hauling up mountain guns.

Involved in the fall of Corizza were six Italian divisions, about 72,000 men. Their mechanization was their undoing in the narrow, muddy mountain passes where they stuck out Italy's neck into Greece. Like the riflemen behind trees who played hob with the British regulars in 1776, the Greek mountaineers from their hilltops demoralized an army which had been told that the Greeks would be pushovers, in fact would probably welcome Fascism with open arms. When Mussolini spoke, promising that Greece's back would be broken (TIME, Nov. 25), the Greeks continued pressing, working with geography instead of against it. Frantically, the Italians called on their Air Force to strafe and disperse the attackers, and for a day or two there was carnage around Corizza. Then the R. A. F. arrived to bolster the gallant but rickety Greek Air Force. In a few hours, Spitfires and Hurricanes smacked down so many Italians that toward the end of the battle not a Fascist wing dared come across that sky.

With painful talk about "moving on schedule to other positions," the Italians evacuated the city, leaving behind warehouses full of equipment. Perhaps by the standards of modern warfare the booty was not great, but to the Greeks, accustomed to eating bean soup and black bread and carrying hand-me-down arms, it was immense. This plunder was, after the strategic factors and the enormous boost to Greek and British morale, the third most important thing about the fall of Corizza. It was said to comprise enough small arms and ammunition to outfit two Greek divisions, more heavy artillery than the entire Greek Army had when the war began. There were 80 field pieces, 55 anti-aircraft guns, numerous machine guns. There were 20 tanks, 250 trucks and other autos, 1,500 motorcycles and bicycles, 10,000 blankets, several thousand tons of wheat. Fortunately for the Greeks, the Italian ammunition fitted their rifles.

Straightway the exultant Greeks hopped into captured tanks to chase the retreating Italians up the road to Pogradec, where Italian General Ubaldo Soddu, after cashiering some 50 senior officers, tried to form a secondary defense line. Another Greek pursuit column harried the Italian retreat toward Moskopole ("Perfumed City"). Greek and British warplanes bombed and machine-gunned long columns of dejected Blackshirts and Alpini, whose welfare was further menaced by mutinous Albanian battalions in their very midst, by Albanian snipers, knife-men, rock-rollers and bridge-blasters in the gorges and ravines along the way.

The miserable Italians dared not light camp fires at night; some subsisted on raw mule meat. They took refuge as they went in churches and mosques, using them as makeshift forts. Neutral military observers said that if only Britain could send enough planes, the Italian Armies might be swept into the Adriatic before Rome could get set for a new offensive. Fascist reinforcements moving up to Pogradec met their pell-melling comrades on the road out of there, turned and fled with them as Pogradec fell. The same thing happened at Moskopole and it looked as though the first stand General Soddu could make would be on a line from Elbasan on the Shkumin River, which cuts Albania in two roughly equal parts, down the Devoll River to Valona. The way things were going last week, the southern part of Albania would soon be mostly Greek, which in fact it is culturally and racially. At glad Corizza, Major Charissiades, heading the new town council, welcomed the Greeks as liberators. Greek flags were brought out of hiding and pictures of Italian King Vittorio Emanuele were burned in the public squares.

In southernmost Albania, also, the tide of battle was at flood for Greece. One Greek column, piercing through from Konitza, swept up the road from Leskovik toward Corizza, mopping up. Another pressed west along the Voiussa River, aiming at Tepeleni. Two other columns swept down the Dhrino Valley toward Argirocastro ("Silver Fort") and over the mountains toward Porto Edda. One more Greek column pushed up across the Kalamas River out of Epirus, driving the last invader from Greek soil and threatening to wipe him out of southern Albania as well. With the Italians in retreat everywhere, the ultimate object of all the Greek columns was to cut off their foe from his ports of escape.

So stood Italy's deplorable Balkan adventure last week, and the Greek Army joined the Finnish on a history page reserved for little fellows who knew how to fight for home and honor. But the first round seldom decides a prize fight, and beneath little Greece's jubilation lay some grim facts. Greece faced woeful shortages of almost everything that it takes to fight a war. She lacked meat, wheat, oil, coal, sugar. Her chief sources of income—shipping and tourists—were no more. Her best customer of wine, olive oil and tobacco was Germany. Only Turkey and Great Britain can help her, and the latter has its hands full helping itself.

Last week a steady stream of war matériel was flowing, much of it by air, from British bases in the lower Middle East to new ones in Greece. Some said many Australian and New Zealand troops were going, too, though Britain denied this, saying her only ground troops in Greece were military police and air-base guards. But besides military help, Greece was going to need food, fuel, money. Over her loomed not only the shadow of Germany on the northeast but cold and hunger at home.

(«Time», Monday, Dec. 02, 1940)

Ever since Poet Homer gave the lowdown on Ulysses, wily has been the word for Greeks. The Greek syndicates of gamblers; the late Sir Basil Zaharoff, merchant of death; tens of thousands of Greek traders in fruits, tobaccos, steamships have carried on the Ulysses tradition of wandering, guile and gain. Last week, with their mother country menaced, Greeks all over the world went in their own ways to her support. In the U. S., one of them was a millionaire oil operator of Louisiana and points west. Possessor of a 65-year exclusive franchise to find and exploit Greece's petroleum resources, he turned over to Premier General John Metaxas $1,000,000 worth of tools, trucks, pipeline, drill rigs, explosives and a 38-ton tank with which he and his men had been working in the Peloponnesos. His name: William Helis of New Orleans.

The Helis family belongs in Arcadia, high in a mountain district which not even the terrible Turks ever conquered and from which come some of Greece's ablest highland fighters. William Helis' grandfather was mayor of their town for 32 years. Young William went to America after finishing secondary school, did odd jobs in New York and Milwaukee. In 1908 he married a Philadelphia girl of Dutch descent, who bore him three daughters and a son. He set up a coffee and spice business in Kansas City, Mo., became a top sergeant in the National Guard in World War I. Then he hunted for oil in Texas — and found it, near Wichita Falls. He found more in Oklahoma and in California. In Louisiana he struck it really rich because he found not only plenty of oil around New Iberia but also Robert Maestri, cagey political boss of New Orleans.

Now that his mother Greece is up against it, Oilman Helis' fortune is at her disposal. He is director of the southern activities of Greek War Relief Association, Inc., which has offices at No. 730 Fifth Ave., Manhattan and of which Harold Stirling Vanderbilt is national honorary chairman. Mr. Vanderbilt, no Greek, is in there for humanitarian reasons but he and Mr. Helis, the Greek boy who made good, have something in common: Mr. Helis has a 107-ft. yacht, the William Helis II, and Mr. Vanderbilt is the U. S.'s most famed yachtsman.

Spyros Skouras, chain cinema tycoon, is national president of the Greek War Relief Association, Inc., which hopes to raise $10,000,000.

(«Time», Monday, Dec. 09, 1940)

Snow sifted last week through the mountain peaks and troughs of perpendicular little Albania. It laid a white blanket over thousands of stiff dead Italian soldiers on bleak slopes and in forested ravines from Porto Edda, where many of them had landed, northeastward to Lake Ochrida and the east-west gorges of the Shkumin River, where Italian commanders strove to make a stand against the relentless, amazing Greeks. Most Italians abhor cold as they do the sharp Greek bayonet, which Rome last week plaintively called a "barbaric and inhuman" weapon.

To Albania, to improve the shattered discipline of the routed, retreating Blackshirts, hurried fierce, sporting Achille Starace, former Secretary of the Fascist Party, now chief of the Fascist Militia. Mussolini's mouthpiece, Giovanni Ansaldo, took pains to announce over the radio: "We must win the war in the Mediterranean with our own Army, quite alone." Crown Prince Umberto himself condoned with the families of the first victims of the Greeks.

The red-faced Italian High Command tried again to laugh off continued Greek advances. The enemy, it was said, was merely capitalizing on a "strategic retreat" by an expeditionary force that had had the bad luck to run into dirty weather. To prove that everything was going "according to prearranged plan," General Ubaldo Soddu, who was rushed out last month to replace Commanding General Sebastiano Visconti Prasca, was upped last week from corps commander to Army commander and confirmed in his post.

His most vital problem was one of logistics—getting hundreds of trucks full of food and ammunition daily over hundreds of miles of tortuous mountain roads to supply the over-extended forces. Next he had to bring over from Italy whole new armies to replace the beaten Ninth Army in the north and the newly arrived but already disorganized Eleventh Army in the south. Meantime, Greek and British bombers hammered at the landing places, rendered Valona and Durazzo "almost useless" in the wake of the new arrivals, threatened to cut off their supplies and redouble General Soddu's problem. British ships came up and shelled Porto Edda. Daily Allied airmen, through fair weather and foul, bombed and strafed the crawling lines of Italian supply trucks, against which Albanians also sniped and sent down rock falls.

On to Argirocastro. Territorially the war progressed little during the week, and only the Greeks moved forward. They clinched their hold on Pogradec in the northeast, thus consolidating their capture of Corizza last fortnight, and giving them a north anchor for the lateral road paralleling the Greek border clear down to the southern Albanian coast. Up & down this road Greek Generalissimo Papagos could swiftly shift his strength in or out of any of the mountain troughs, slanting northwest-southeast, through which the scattered Italian Eleventh Army last week fought rear-guard actions in its withdrawal up to the line from Valona to Elbasan. Next major Greek objective was the Italians' southwestern base, Argirocastro, defended by an Italian "battalion of death" fresh from Modena. The Greeks, attacking before dawn after nocturnal artillery barrages, smashed their way by grenade and bayonet up the eastern wall of Argirocastro's valley. This week, on the central front, the Greeks claimed the capture of 5,000 prisoners in a major rout.

High Fliers. Italy's erratic Air Force, so noticeably deficient in the campaign's first month, made a great show of trying to support its ground troops last week. One day at least 300 planes were at work. They heavily bombed Florina, the northern Greek base back in the Pindus Mountains whence most anti-aircraft defense guns had been moved forward with the Army. But over the actual fighting fronts and Greek supply lines, the Italian fliers stayed at least 10,000 feet up, to avoid hitting mountain peaks or being hit by Allied A.A. fire. Two miles is no height for nervous bombers to hit machine-gun or artillery emplacements, or vehicles moving on narrow, winding roads.

Unless Germany should suddenly throw in some effective air power, Italy's payoff in Albania, now that snow was falling, looked at best like a stalemate for some months, a lasting disgrace and a drain on the entire Italian military establishment. If, operating from their new strongholds in Crete, British naval power could gain mastery of the Adriatic, past minefields and submarines, the entire Italian expedition, including last week's reinforcements, might be annihilated, or forced to execute a sorry withdrawal like the British from Norway.

"Children of Socrates." Bravely over the sandbagged Parthenon last week, as November ended and bitter winter began, flew the blue & white flag of Greece. And bravely through the world, Minister of National Security Constantine Maniadakis, right bower of Premier General John Metaxas, appealed for aid in the struggle to come. Said he: "We address ourselves particularly to the great, strong, liberal union of the United States of America. We pay no attention to the enemy's material strength, and neither do we dare pay attention regarding the intentions of other probable enemies [Germany] . . . the children of Socrates, Plato and Aristophanes are prepared for any ordeal . . . to die rather than submit."

In London, Secretary of State for India Leopold Stennett Amery put the brightest of all faces on the historic stand of Greece. Said he: "If we can enable Greece to hold her own until we have disposed of the Italians in Egypt, we shall have secured for our armies a foothold from which we might threaten the flank of any German attack on Turkey.

"From that foothold we might eventually, with our own armies and new allies whom our growing strength will gather, deal a mortal thrust at the German dragon, not against the scaly armor of the Siegfried Line, but against his soft underside."

(«Time», Monday, Dec. 16, 1940)

(See Cover) The Greeks poured on. Pushing northward to Porto Edda, they crossed the marshes above Lake Butrinto which the Italians had thought were impassable. They waded armpit-deep through icy water, pushing their guns on rafts. They crawled over the mountains from the east, cut the road to Delvino and planted their guns on the heights above Porto Edda. The Italians set the town afire and retired up the coast road, leaving to the Greeks a destroyer (damaged by British bombs) which had taken refuge in the harbor.

Fifteen miles over the hills, the Greeks had taken all the heights surrounding Argirocastro. There the Italians also fired the town and fled up the road toward Tepeleni—harassed by snipers and artillery from the hills above. Before the Italian rear guard of tanks retired, the Greek infantry stormed the town. They dropped from balconies on to the roofs of tanks, threw hand grenades into the openings, jammed the tank-tread mechanisms with their bayonets.

In Athens people danced in the street by moonlight, carrying at the head of their procession the victory flag that had been flown on the Parthenon. First Corizza, then Porto Edda, then Argirocastro —the three advance Italian bases in Albania—now side by side over all three flew the double eagle of Albania and the blue and white banner of Greece. The Greeks rejoiced and the world was stunned.

War is always full of surprises, and afterwards the explanation of how they occurred gradually leaks out to the outside world. The first surprise of World War II was the German conquest of Poland in 27 days—explained by the inferior Polish materiel and the rashness of the High Command and the German development of Blitzkrieg tactics with tanks and planes. The second was the swift German conquest of Norway—explained by fifth-column activity and the elaborately daring German plan of invasion. The third was the German sweep through the Low Countries and France, an elaboration of Blitzkrieg tactics with Panzer divisions, planes, parachute troops, deception, fifth columny all used with symphonic mastery.

Even before the third surprise was complete, the fourth surprise had taken place. A British Army of 400,000 men, all but surrounded in Flanders, succeeded in effecting its escape by sea from Dunkirk—explained by dogged British courage, the reckless brilliance of British seamanship, and the ability of the Royal Air Force to maintain local command of the air. The fifth surprise took place no one knew exactly when—when Hitler found his forces unable to undertake a direct assault last summer on Britain herself. The explanation has never been completely given, but it included as its chief ingredients the ability of the R. A. F. to inflict devastating punishment on German daylight bomb ers and to upset German preparations for invasion across the Channel.

But none of these surprises was greater than Surprise No. 6: the ability of ill-armed Greeks to fight off and defeat the well-armed and more numerous Italians.

The methods and the tactics which made this possible were last week becoming apparent. They could be summed up in one military moral : the Greek Army knew how to use what it had. For example, it is said that one bomb tipped the scale at Corizza. Knowing that Italian reserves were being rushed along a certain road, a Greek general sent for some of the few British Blenheims available to him. They arrived in time, knocked out a bridge over which the Italians must pass, machine-gunned the halted column on the far side. Only one of the three Blenheims returned from that foray but the trick was turned.

Little John & the Parrot. Up from Athens last week to assay the situation and decide whether his troops should dig in for the winter pretty soon or try to strike on through, drive the Italians into the Mediterranean before they could poise a counterblow, went the long-nosed, aristocratic Commander in Chief who taught and led the Greek Army: General Alex ander Papagos (paa-paa-gos). Every morning, for two hours at Army Head quarters in Athens, he had conferred intently with Premier General "Little John" Metaxas. His enemies derided General Papagos as "Little John's" Papagei (parrot), overlooking the fact that the relationship between the two men is much like the Foch-Weygand relation: master and disciple.

Dumpy, round-faced Little John, now 69, learned his soldiering in Germany; lean, bat-eared Alexander, 57, learned his at France's Ecole Superieure de Guerre. Both suffered the pangs of Greece's sorry war with Turkey in 1922. Out of that defeat came their resolution to do better another time. Often the loser in one war wins the next (witness France after 1870, Germany after 1918). As Chief of Staff, General Papagos saw to it that Greece's 18-month compulsory training for all males between 21 and 50 was no child's play. King George II, after his restoration in 1935 by a military junta of which Papagos was a member, made the Army popular by insisting on clean barracks. But it was the combined, concentrated brains of Metaxas and Papagos which evolved the mountain strategy and tactics now bearing such startling fruit. Last week Norwegian mountain troops journeyed from Great Britain to get in on the Greek show, and the Swiss applied for permission to come and take notes.

Meticulous is the word for General Papagos. In private life a patrician to his long fingertips, a foppish lover of fine horses and a patron of racing, his lifelong study has been a huge collection of military books. John Metaxas' name went upon the defense system thrown up along the Bulgarian and Yugoslav borders, which were later extended hastily down the Al banian. But in General Papagos' head rests knowledge of every gully and goat track not only in the Greek mountains but far beyond. Like his soldiers, whom amazed correspondents found toiling with out lanterns at midnight to repair bridges, he can thread the Balkans blindfolded.

On occasion he works out each move, for platoons as well as divisions, in minutest detail before ordering it.

Fascist propagandists have insisted that their Greek debacle was caused by the perfidy of Albania and Albion, by "bad luck" (early rains) and by Greek treach ery in being all mobilized and ready in numbers far greater than Italy could get to the front.* The last part of this lame story is obviously untrue, but it may be that behind the beard of many an "Al banian" who incited his comrades' sur render or rebellion grinned the sly face of a British Intelligence operative. But the fact remains that Italy threw into the fight, at the outset, ten full divisions numbering, with supply and labor troops, over 200,000 men, to which two more divisions were added after the going got rough. These included many celeri (mobile) units. At the Pindus passes the invaders were confronted by not more than eight divisions out of the 13, plus one of cavalry, which Greece could mobilize but of which she could equip only ten for fighting. Not even numbers of airplanes made much difference, for Italian planes outnumbered the Greeks (even after the British based squadrons at Larissa, Athens) by at least 500 to 100, new planes versus old. And in artillery the Fascist advantage was estimated at 919 guns to less than 100.

Thermopylae in Reverse. 2,420 years ago, 1,400 Spartans, Thebans and Thespians, occupying a narrow mountain pass above the sea, were surprised from the rear by a large Persian detachment clambering around through the hills. Spartan King Leonidas and his men fought stubbornly for several hours, but all (except the Thebans, who surrendered) were annihilated. The Spartans at Thermopylae were great heroes but they lost the battle.

General Papagos' tactics of 1940 are basically the Persian tactics at Thermopylae and his troops too have repeatedly taken the long, hard way around through the mountains to attack the Italians from behind and above.

With their mechanized equipment, their heavier and more numerous artillery and their larger number of troops, the Italians naturally stuck to the roads, and the roads run through the valleys and the passes. General Papagos made use of the mountains by moving along the heights to outflank the Italians. His infantry, composed of mountaineers — all Greece is mountainous — knew exactly how to get through hills. Everything fitted.

Even the Greek shortage of artillery, particularly heavy guns, was turned to advantage. They dragged their light mountain pieces over rough trails and got into position where they could drop shells on Italians who could not see them. The effectiveness of these tactics was immense. Proud of their artillery, the Greeks thought it was an immense good omen when Përmet fell on the feast day of Saint Barbara, patroness of artillerymen.*

Only of simple equipment — rifles, hand grenades, bayonets — did the Greeks have reasonably adequate supplies, and of these they made the best. Military experts agree that the bayonet and hand-to-hand fighting are out-of-date in modern war, but the Greeks found use for them. Advancing through the mountains, they repeatedly stormed small positions held by Italian detachments who had been sent out to safeguard the flanks of columns on the roads below. Time and again, Greek bayonet and grenade proved conclusive.

The Finnlike toughness of the Greek soldiers was a final factor in what happened. The Italian peasant is not accustomed to a life of luxury, but Greek mountaineers live on even less. They ordinarily subsist on a little cheese, a few olives, goat's milk, a swallow of resinous wine, black bread and a few leeks. To them the hardship of mountain campaigning, far from field kitchens and services of supply, is hardly more than an inconvenience. The evzones or elite guards (who wear khaki kilts in battle, not their white dress fustanella and red pomponned slippers) are chosen for stature, and of them there are five regiments. The rest of the troops are wiry little men, averaging less than 5 ft. 5 in. Observers marveled at their endurance on long night marches up blizzardy mountains, through slushy defiles; their sleeping on cold rocks or in frozen ditches; their unfailing grins and cheery chatter before, during and after battles. In every way the poverty of Greece had given it strength and the Greek Command knew how to capitalize upon it.

The Course of Battle. With the fall of Porto Edda the Italians were left with only three ports to bring troops and supplies into Albania:

>> Valona, a windy harbor with two wharves with shallow draft.

>> Durazzo, a shallow harbor full of shoals, with one good pier.

>> San Giovanni di Medua, a primitive harbor, where ships anchor to a sunken hull.

Between them there is a connecting coast road, but the roads to the battleground (see map p. 29) lead diagonally into the interior with hardly a passable crossroad, so the Italian column operating in each valley is practically isolated from every other column and dependent on one sole route for supply. Greek supplies come up the other end of these roads, but they have some intercommunication via the lateral Corizza-Ioannina road.

Furthermore the Greeks, advancing on the mountain ridges, were in a position to attack the Italian lines of communications broadside on. The extreme Italian left, after yielding Pogradec and retreating up the west shore of Lake Ochrida, was in a particularly awkward position. Greek mules and shock troops pressed simultaneously along the Mokrë Mountain ridge and down the Devoll River Valley to try to cut those lines near Elbasan. Should they succeed, the Italian Ninth Army of the north would be in danger of encirclement, annihilation.

If this took place, the Greeks might be able to drive into the coastal plain. Whether it would profit them to do so will depend on whether the British can lend effective air support to prevent strong Italian reinforcements from being landed.

Whether the Italians will be able to form a strong defense line before they are pushed entirely out of the mountains remains to be seen. Even if they are not able to do so General Papagos may find it wiser to halt his advance on the edge of the higher mountains. In that region he would not lay his armies open to Italian mechanized attack; he might be able to cut the pipeline on which Italy depends for Albanian oil; he would also have strong defensive positions in the mountains; and his army would not be too far extended if the Germans come to the Italians' aid by marching down through Yugoslavia and Monastir to attack his rear.

Scapegoat elected for Mussolini's Albanian fiasco was white-haired, crinkle-eyed Marshal Pietro Badoglio, Chief of the General Staff, universally recognized as Italy's sagest soldier. He had opposed the Greek venture. Germany's Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel is also said to have opposed the Pindus push, recommended instead a sudden naval encirclement with multiple landing parties, such as Germany sprang on Norway. Being obliged to cons jit Keitel last month, to be told how to retrieve his subordinates' botch of a campaign which he never approved, must have made the 68-year-old Marshal swallow hard. Last week he retired "at his own request" from the service of a Duce whom he once offered to crush as an upstart.